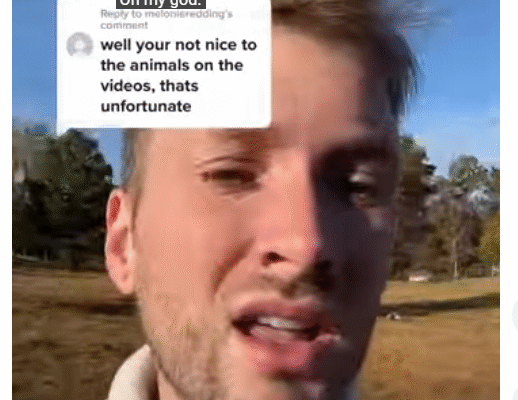

Replying to @melonieredding: “Tell me you’ve never had farm animals without telling me you’ve never had farm animals.”

That comment. That’s the one. That’s the comment you post from a clean sofa, probably with a scented candle burning, after seeing a curated Instagram photo of a highland calf that looks like a stuffed animal.

You see a “simple life.” We see a 24/7/365 job where your “employees” are creatures whose sole purpose, it seems, is to find the most creative and expensive way to die, usually in the middle of a blizzard at 3 AM.

The fantasy you’re picturing—waking up with the gentle sun, sipping coffee on a rustic porch, watching serene animals graze in a dewy pasture—that’s a vacation, not a vocation.

The reality is an alarm clock blaring at 4:30 AM, not because the rooster crowed, but because you heard a single, panicked bleat from the barn that sounded wrong. It’s discovering the electric fence is down again and the pigs are halfway to the highway. It’s cracking a half-inch of ice off the water troughs with a sledgehammer when it’s 10 degrees out, your fingers aching and numb, all before you’ve even had that first sip of coffee.

There are no “days off.” You can’t call in sick when a sudden front is rolling in and 200 bales of hay are still on the field. You can’t “work from home” when a ewe is in hard labor and the lamb is breached, meaning you have to sanitize, glove up, and stick your entire arm into an animal to save two lives, all while kneeling in manure and straw.

This is the part you truly don’t get: you see “pets.” We see “livestock.”

That doesn’t mean we are cruel. It means we are realistic. Good stockmanship is about providing the best, safest, healthiest life possible for that animal, but it is a life with a purpose. When you have 300 chickens, you don’t name them. You don’t cry when a hawk swoops down and takes one; you get angry that you have a breach in security and work to fix it.

You learn to spot the slightest limp or a head held just a little too low, because that could mean foot rot, or coccidiosis, or pneumonia—any of which could wipe out half your investment and all your hard work. You bottle-feed that rejected calf for eight weeks, you treat its scours, you rejoice when it finally thrives… and then you load it on the trailer for the auction.

That is the job. It’s not a petting zoo. It’s agriculture.

You’re not picturing the smell. Not the good smell of hay, but the metallic tang of blood, the sticky, sulfurous odor of hoof rot, or the unmistakable, sweet-sick smell of infection from a ruptured abscess. You’re not picturing the mud. Oh, the mud. It’s not just “dirt.” It’s a soul-sucking combination of clay, urine, and spilled feed that will steal your boots and tries to break your ankle every single day from November to April.

So yes, @melonieredding, you’ve told us all we need to know. You’ve never had to make the call to put an animal down because the vet bill would be $2,000 for a $200 animal. You’ve never had to cull a “cute” but aggressive rooster that’s injuring your hens.

We love this life. But we love the reality of it—the grit, the heartbreak, the exhaustion, and the resilience. Not the storybook fantasy you’re selling.